With the 2020 NFL Scouting Combine starting today with measurements and interviews for wideouts, tight ends and quarterbacks, we are officially knee-deep into draft season.

This is a season of hope for all teams, and rightfully so, as draft success or failure can significantly alter the course of a franchise. Look no further than the Seattle Seahawks, who managed to draft Earl Thomas III, Kam Chancellor, Richard Sherman, Bobby Wagner, K.J. Wright and, most importantly, Russell Wilson within three consecutive drafts from 2010-12 and went on to have one of the most dominant four-year stretches that we've seen from an NFL team.

What we shouldn't forget, though, is that such a turnaround usually takes more than one year, even if a team finds multiple future franchise cornerstones in one draft. The reason is that every player's NFL career starts with a steep learning curve. In other words, rookies generally produce less in their rookie year before making a huge leap in Year 2.

Thanks to PFF WAR, a metric developed by PFF data scientist Eric Eager, we can now measure how much a player is worth in terms of winning football games, which is what ultimately matters for teams and fans across the NFL.

We found that the players of the vaunted “Legion of Boom” needed a year of acclimation before maximizing their contribution to the Seahawks' success, as Thomas, Chancellor, Sherman, Wagner and Wright added a total of one win above replacement during their respective rookie years before averaging roughly double that amount over their second, third and fourth years in the league.

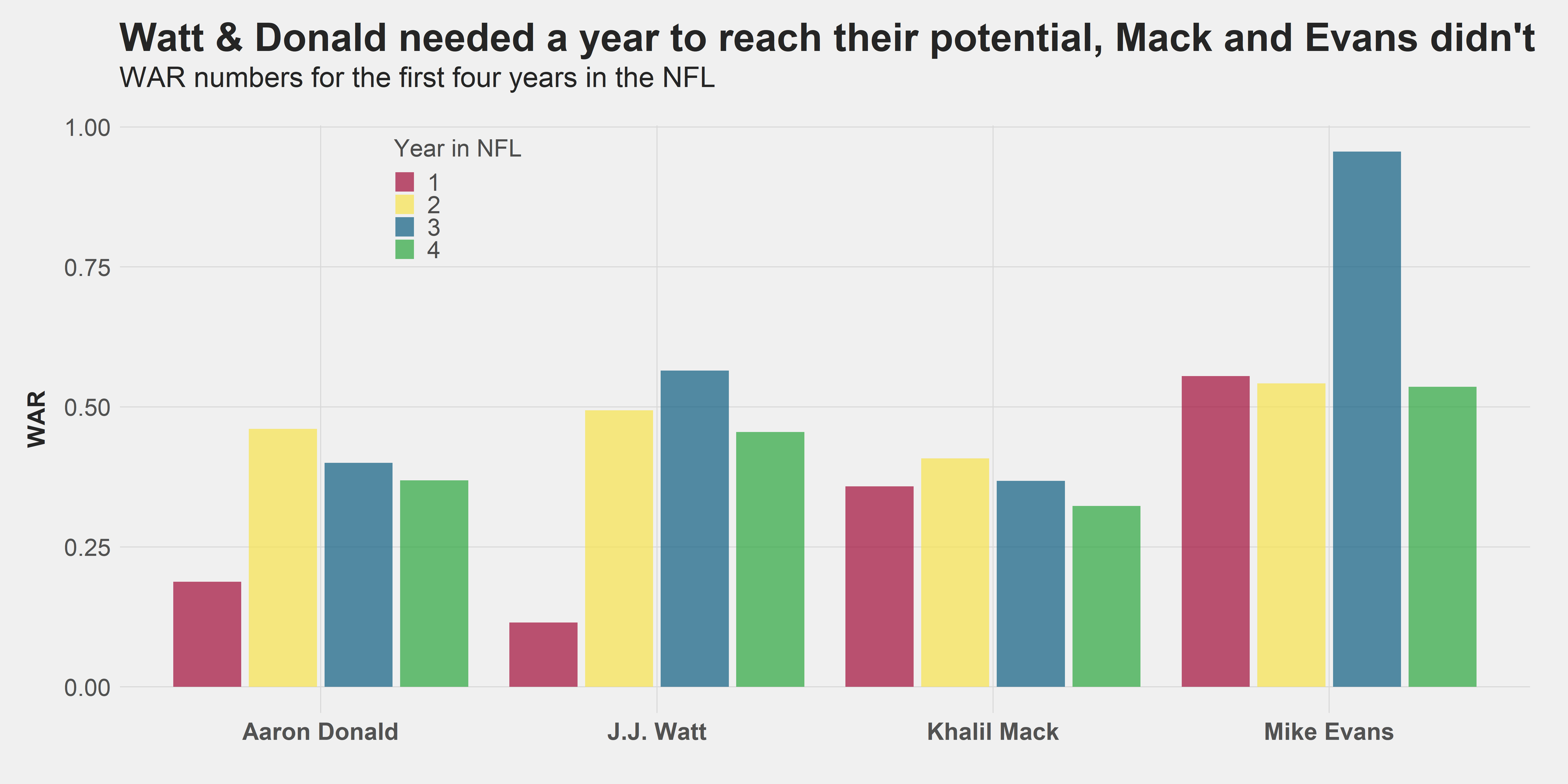

We observe the same even for generational players like Aaron Donald and J.J. Watt. However, there are also the cases of players like Khalil Mack and Mike Evans, who didn't need any time to acclimate to the NFL.

Rookies increase their production by 75% after their rookie year

While it shouldn't be news to anyone that rookies generally don't operate to their full potential straight out of the gate, the interesting part is the exact shape of the learning curve. Both Donald and Watt excelled in Year 2 and basically held their level going forward. When considering all players through their first four years in the league during the PFF era, i.e., all players drafted between 2006 and 2016, we find the same pattern.

Reminder that an unproductive rookie season isn't the end of the world. Players tend to increase their production by 70-80% after the rookie year.

Also a good reminder that a turnaround via the draft usually takes at least two years. pic.twitter.com/mjU0s1FocC

— Moo (@PFF_Moo) February 17, 2020

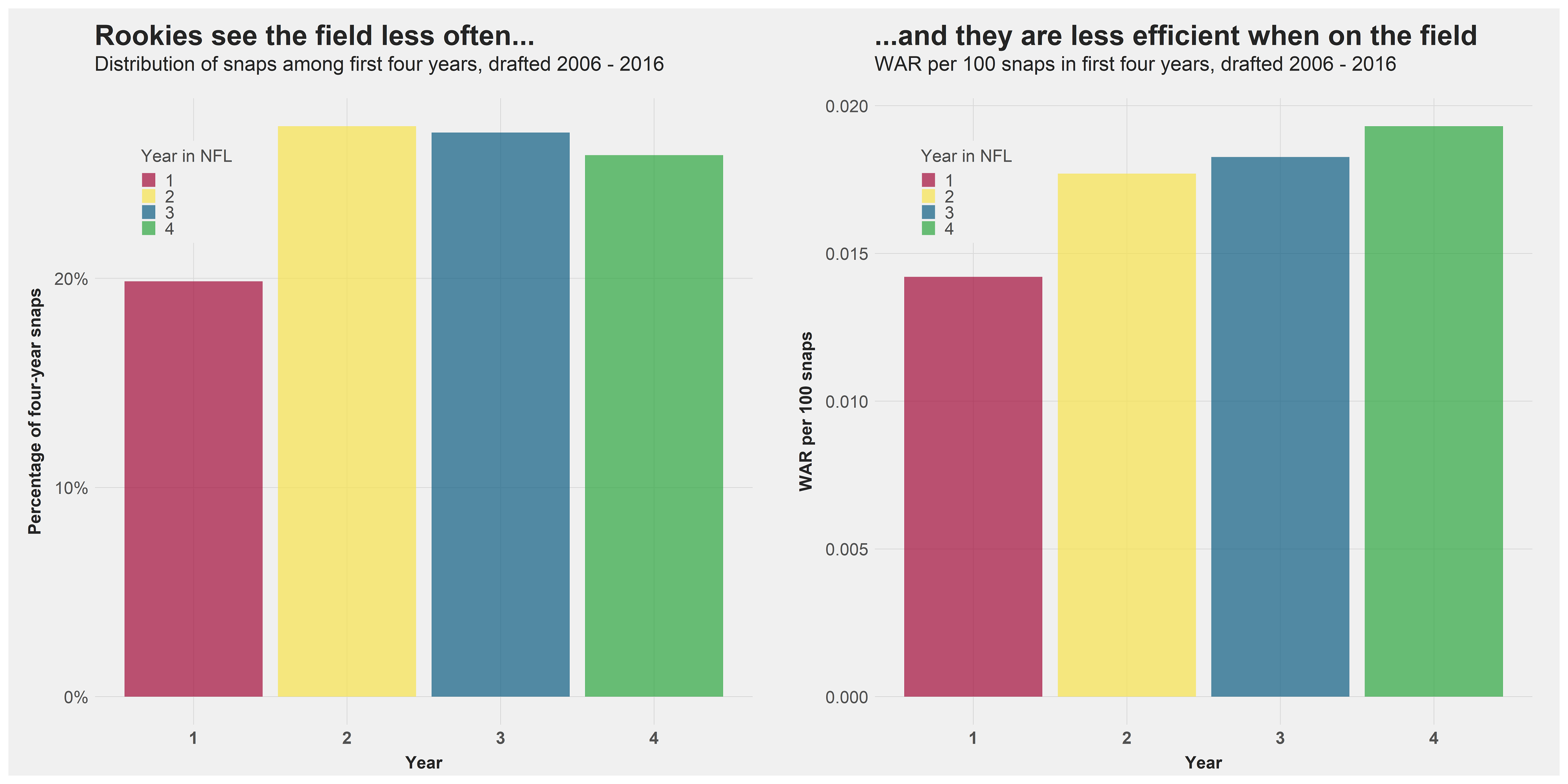

Young players tend to increase their production by roughly 75% going into their sophomore year, and they generally hold their level from there. Only 16% of the total WAR that is generated by all players through their first four years in the league comes from rookies, as opposed to roughly 28% in each of the next three years. This suggests that one shouldn't necessarily worry when a player either struggles to see the field or struggles to produce when on the field in his rookie year. However, it might be time to start getting anxious when the player repeats his struggles in Year 2.

We note that PFF WAR depends on both per-play efficiency and volume, so the natural question is which of the two factors drives the effect? The answer is that both factors play a significant role, as rookies tend to get less playing time and apparently rightfully so, as they also produce less value when on the field.

© 2024 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2024 PFF - all rights reserved.