NFL draft prospects are frequently framed as “polished” and “pro-ready” or “raw” and “athletic marvels.” While there are issues with these framings, there is a kernel of truth to the sentiment. Broadly, prospects are evaluated for their athletic prowess and their refinement in particular techniques. Many philosophical debates revolve around which ought to be more valued.

So today, we will be applying this idea to edge defender prospects to determine where they may be drafted as a result of their athleticism and their final season production. This will allow us to get an idea of prospect caliber, where they may be selected and glean some information as to which should be more valued in NFL edge defender prospects.

We received athletic testing numbers from the NFL combine and, when possible, missing data was filled in with pro day measurements. In the event where a player did not complete an event at either the combine or his pro day, it was assumed the player would perform at the position average since 2017 among combine participants. These measurements and times were then thrown into a random forest model to handle potential nonlinearities and complex relationships between variables to predict draft position. While the exact results will not be reported here, it is worth mentioning that the model prioritizes heavier, longer and more explosive players over shorter, lighter and faster players.

We additionally modeled draft position based strictly on PFF's production metrics using a random forest model. However, since many production metrics relay overlapping information (i.e. pass rush win rate and pressure rate), the metrics first underwent a principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensions of the dataset. This allows the model to base its prediction only on the most explanatory combination of metrics. An indicator for whether or not the player was in a Power Five conference was also added. The only noteworthy PCA result is that the metrics that evaluate pass rushing and run defense are nearly orthogonal, and thus, we can consider them nearly completely independent skills in our analysis. Both volume — such as sacks and stuffs — and rate statistics —such as pressure rate and run defense win rate — were considered.

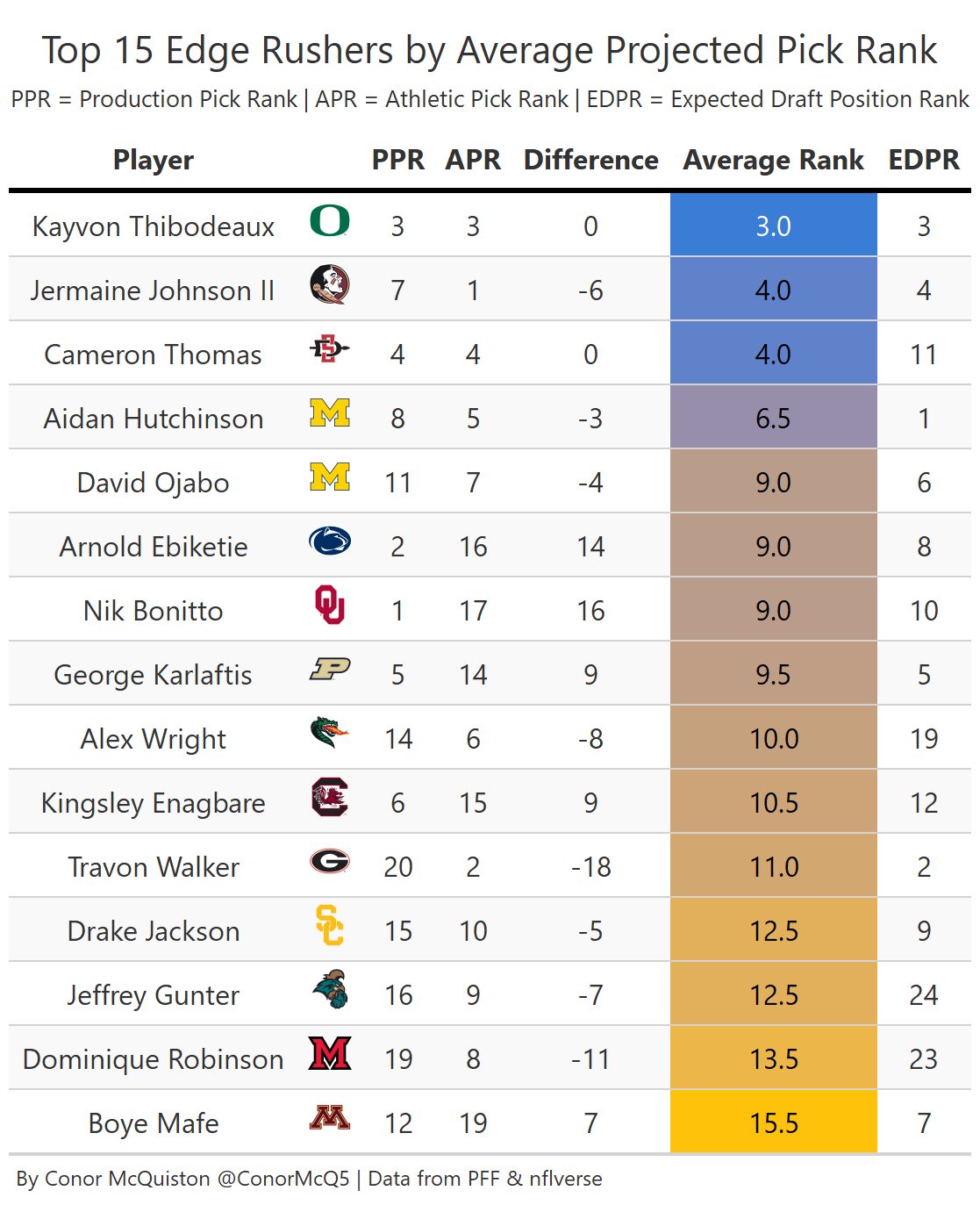

Using the past five drafts (2017-2021) as our training set, who can we expect to be the first 15 edge defenders selected in this class based on these two models? Note that these models are not well calibrated to the individual pick number since that depends on contextual factors (such as strength of the surrounding class, individual team compositions, QB class caliber, etc.) so instead, we will be reporting how the player ranks within the class.

Before we discuss this table further, let's dive into the outliers compared to the public consensus — Cameron Thomas, Alex Wright and Travon Walker.

Before we discuss this table further, let's dive into the outliers compared to the public consensus — Cameron Thomas, Alex Wright and Travon Walker.

Thomas and Wright are the same story, as they only completed the bench at the combine, and when assuming average times and measurements across the other events at their size, they shot up the boards. In reality, they likely would score below average in at least one event, putting them into a more realistic range. Thomas has the additional benefit where his stellar production metrics do not fully account for the varying level of competition he faced in the Mountain West.

Walker, on the other hand, is identified as one of the premier athletes in the class while being one of its least productive players. His lack of production has been noted repeatedly, but it is worth noting that he did not grade particularly well under PFF’s schema despite his stellar technique in the run game. Additionally, his tackle-based metrics against the run (stops and stuffs) were artificially lowered as a result of playing with a legendary front seven at Georgia.

With those outliers noted, we can categorize most of the remaining players into two groups: those who were much better producers than they were athletes and those who were much better athletes than they were productive. It is not immediately obvious which group of players are more likely to succeed in the NFL. Perhaps the better athletes fulfill their potential more often in the NFL, or perhaps the more productive players tend to more reliably shine in the NFL due to their more refined technique.

While this is a topic worth more rigorous study, we can find directional information by looking at historical data. Over the past five draft classes, there have been six players who had much better athleticism than production and were drafted within the top 100 picks — Rashan Gary, Deashon Hall, Chase Young, Clelin Ferrell, Demarcus Walker, and Zach Allen. Within their first three seasons, they started, on average, 41.6% of the games they played in. There have also been seven players who were better producers than they were athletes by the same standard and drafted in the top 100 — Josh Uche, Montez Sweat, Tyus Bowser, AJ Epenesa, Zack Baun, Uchenna Nwosu, and Jonathan Greenard. This group only started, on average, 31.6% of the games they played in over their first three seasons.

There are myriad issues with those specific numbers — notably the lack of uncertainty analysis, not controlling for team strength at position and not controlling for the player’s draft pick. However, edge defenders are shown to be fully developed by their third season, and it gives us directional information on which group of players are more likely to see the field more often. Therefore, we can glean that under this analysis players such as Jermaine Johnson II, Travon Walker and Dominique Robinson may be more likely to be successful than players such as Arnold Ebiketie, Nik Bonitto and Kingsley Enagbare.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.