When the Green Bay Packers travel to San Francisco to try and win the NFC for the first time since their title campaign in 2010, a key matchup will be the 49ers’ pass-rush against the Packers’ pass protection, as this is a classic strength-meets-strength scenario.

After the conclusion of the regular season, the Niners' pass-rushing group ranked third in PFF pass-rush grade and pressure rate and second pass-rush win rate. On the other side of the ball, the Packers ranked fourth in PFF pass-protection grade, behind only the Ravens, Saints and Eagles.

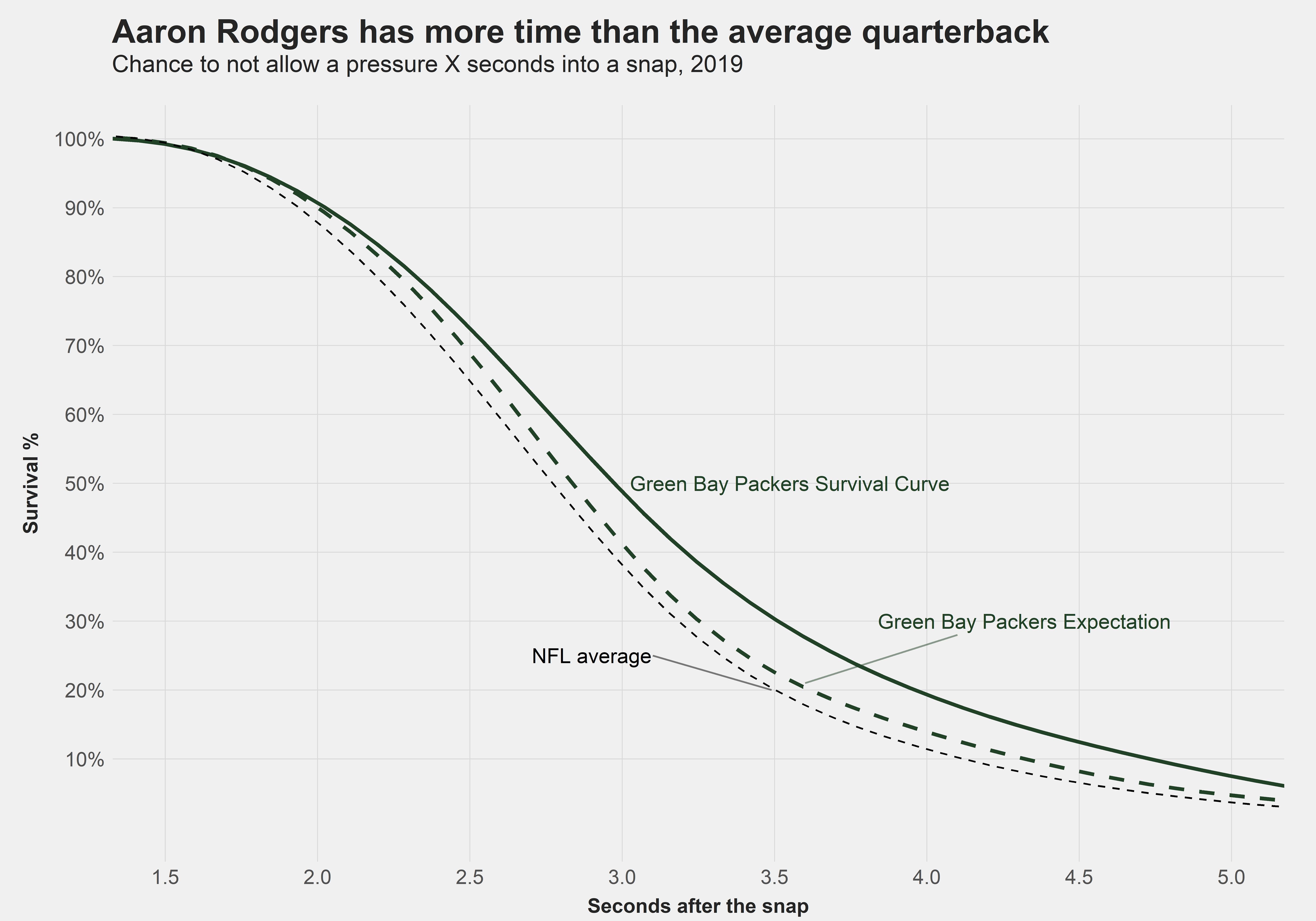

To illustrate the strength of the Packers’ offensive line, we can use the survival analysis that we introduced a few weeks ago. The following chart shows the chance of Aaron Rodgers being pressured at given times after the snap.

We note the Packers' offensive line had a high expectation, mostly because they were blitzed only 26% of the time, the sixth-lowest rate of the league. They also vastly overperformed their expectation and subsequently had the second-best survival curve (measured by the “survival index,” or the weighted mean of the survival rates at all times, as defined in the introduction article), behind only the Tennessee Titans. The Packers’ survival curve isn’t as steep as the average curve, indicating that the pass protection especially excelled later in the snap (starting at 2.5 seconds).

Disruption curves

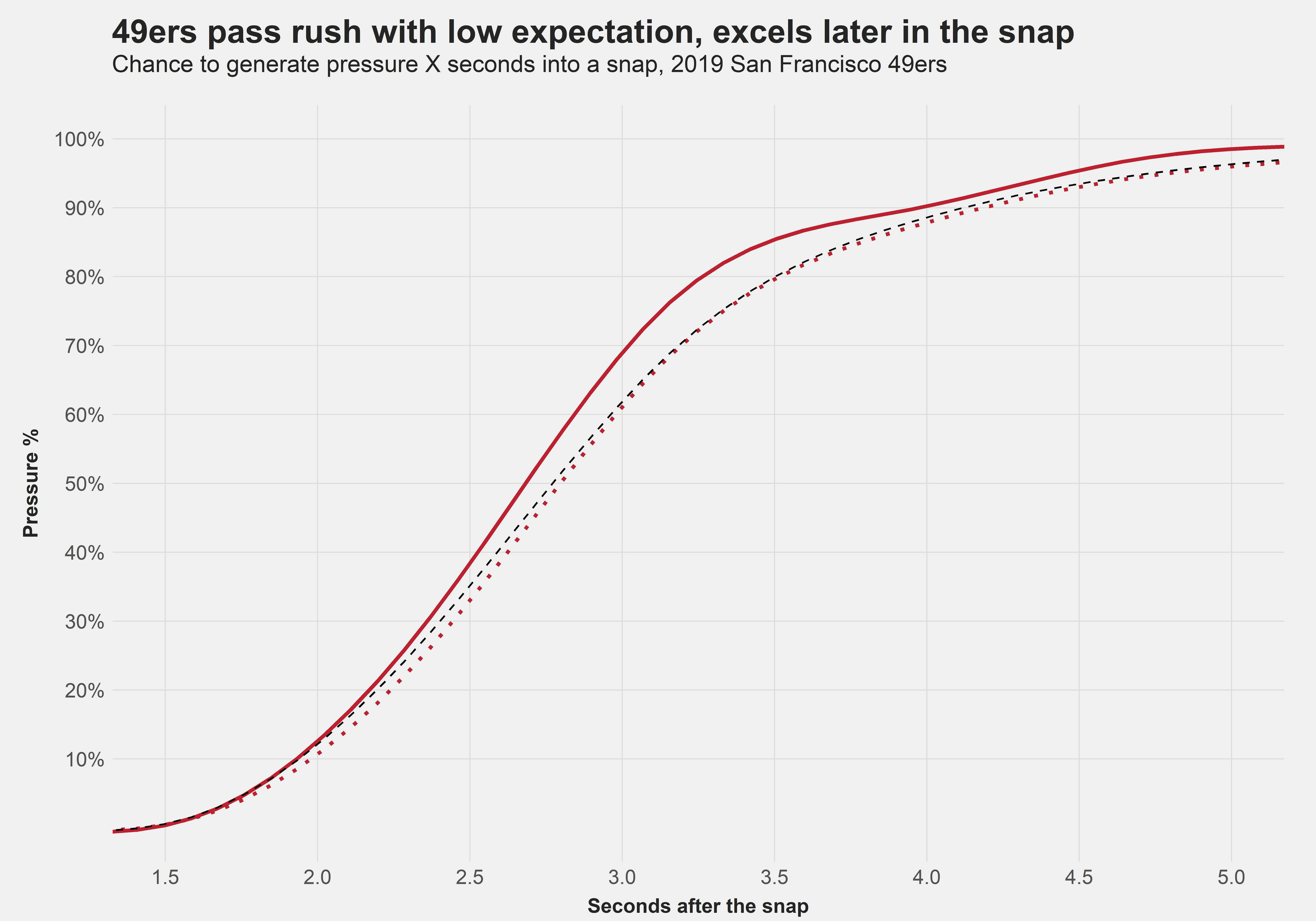

When introducing the survival curves, we reduced our analysis to the offensive side of the ball and didn't look at defenses. However, we will catch up on the pass-rush side of things in this article. Naturally, we'll start with what we will call the “disruption curve” of the San Francisco 49ers’ pass-rush. It shows how likely the 49ers' defense is to generate pressure when the opposing quarterback holds onto the ball for a given amount of time.

Just like on the offensive side of the ball, the dotted colored line indicates the expectation based on the confounders we pointed out in the introduction article, while the black dashed line is the NFL average.

The 49ers blitz their opponent only 22% of the time, the fifth-lowest rate among NFL defenses. Therefore it’s no surprise them with a below-average expectation, especially early in the snap. However, the defensive line is apparently talented enough to overcome the low expectation and still generate pressure at a higher than average rate at any given time. Just like the Packers’ offensive line, the pass-rush unit from San Francisco excels late in the snap, and they don't give the opposing quarterback the comfort of staying in the pocket and going through reads.

Three seconds into the snap, the 49ers generate pressure 9% more than expected, the highest rate in the league. They have also done just as well two and a half seconds into the snap, generating pressure 5% over expectation, second to only Pittsburgh. However, due to their relatively low expectation (28th), their pressure rate at that time is “only” the ninth-highest in the NFL.

Not allowing clean pockets late into the snap could become crucial against Aaron Rodgers, who is used to comfortably standing in the pocket and waiting for his receivers to get open. His average time to throw of 2.74 seconds is the fourth-highest in the league, and on average, it took four seconds for defenses to take him down for a sack this year, the fifth-highest figure of all qualifying quarterbacks. But with Nick Bosa, DeForest Buckner and others chasing him, Rodgers can’t expect to have his jersey kept clean for that long.

The Packers keep Rodgers clean from pressure for the first three seconds more often than any other team apart from the Titans and Ravens. However, if the 49ers do break through, good things will happen for them.

While performance under pressure is mostly unstable, taking sacks and throwing the ball away is a meaningful measure, since it’s more reflective of the quarterback's style than his actual performance. When pressured at three seconds or earlier, Aaron Rodgers takes a sack or throws the ball away 33% of the time, the second-highest rate among full-time starters behind only Kyler Murray; his yards per dropback average (4.2) ranks only 20th in the NFL.

On the other side of the ball, the 49ers rank tied first in the league in yards per dropback (3.4) and EPA per dropback (-0.57) allowed in these situations, and they force a sack or a throwaway at the second-highest rate (30%). This indicates that their coverage is good enough to hold for three seconds, and their linebacker corps — led by Fred Warner, who has a top-10 coverage grade among linebackers with 200-plus coverage snaps — is explosive enough to chase down potential check downs. This is also reflected by the fact that the 49ers have faced the lowest average depth of target (5.7) on throws coming at three seconds or earlier — teams just haven’t found quick holes in the zone coverage developed by Robert Saleh, and they've needed to rely on yards after the catch, which is something that no team can really bank on.

On all other plays — when the opposing quarterback has been kept clean for at least three seconds — the 49ers' defense has been mortal, giving up 0.20 EPA per play that ranks in the middle of the pack among the NFL's 32 outfits. However, caution is warranted when looking at defensive splits, since defense is more noisy than offense in general, and it is especially so in splits. Still, generating (fast) pressure against a quarterback who is almost uniquely used to extended clean pockets is still a tactic that can be crucial to the outcome of the game, as play efficiency generally decreases the faster pressure arrives.

Who wins the battle in the trenches?

We expect the trench warfare between Green Bay's offensive line and San Francisco's defensive line to be crucial to the game outcome on Sunday, so naturally, we are especially interested in which team has the advantage in the strength-against-strength matchup.

Of course, these two teams have met before, and the 49ers not only won the Week 12 game, but they also won the line of scrimmage. They won 16% of their pass-rush reps, which was both more than the league average (11.7%) and more than their own season average (14.4%), and they forced Aaron Rodgers into fast releases (average time to throw of 2.38 seconds), which have rarely been successful for the Green Bay signal-caller. Rodgers also took five sacks in what was his worst game of the season; his passing grade was a mere 51.1 when not pressured and even lower (33.2) when he was pressured.

Of course, a one-game sample size is not meaningful, so we want to investigate the defensive side of our survival analysis in order to find out what we should expect when a stellar offensive line meets a stellar defensive line.

Exclusive content for premium subscribers

WANT TO KEEP READING?

Dominate Fantasy Football & Betting with AI-Powered Data & Tools Trusted By All 32 Teams

Already have a subscription? Log in

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2025 PFF - all rights reserved.